The Epic of Gilgamesh

A Lesson on Mortality, Not Morality

Introduction

The Epic of Gilgamesh, humanity’s oldest surviving epic, originated in ancient Mesopotamia around 2100 BCE and was written in Akkadian on clay tablets. Celebrated for its meditation on mortality and the search for meaning, the epic tells the story of Gilgamesh, the semi-divine king of Uruk, whose journey moves from tyranny to self-reflection. However, while it explores themes of friendship, heroism, death, and legacy, the narrative largely sidesteps Gilgamesh’s abuse of power and lack of repentance, raising the question of whether the epic redeems him or merely immortalizes a deeply flawed ruler.

In considering how the epic frames these struggles, this review takes a thematic approach, examining the recurring motifs of the epic rather than following its chronological plot in order to consider how it portrays human ambition, moral complexity, and the pursuit of lasting significance.

Friendship with Enkidu

Gilgamesh’s story begins by a graphic portrayal of his abuse and tyrannical behavior towards his people; violating women, enslaving men, and imposing his will without regard for the well-being of his citizens.

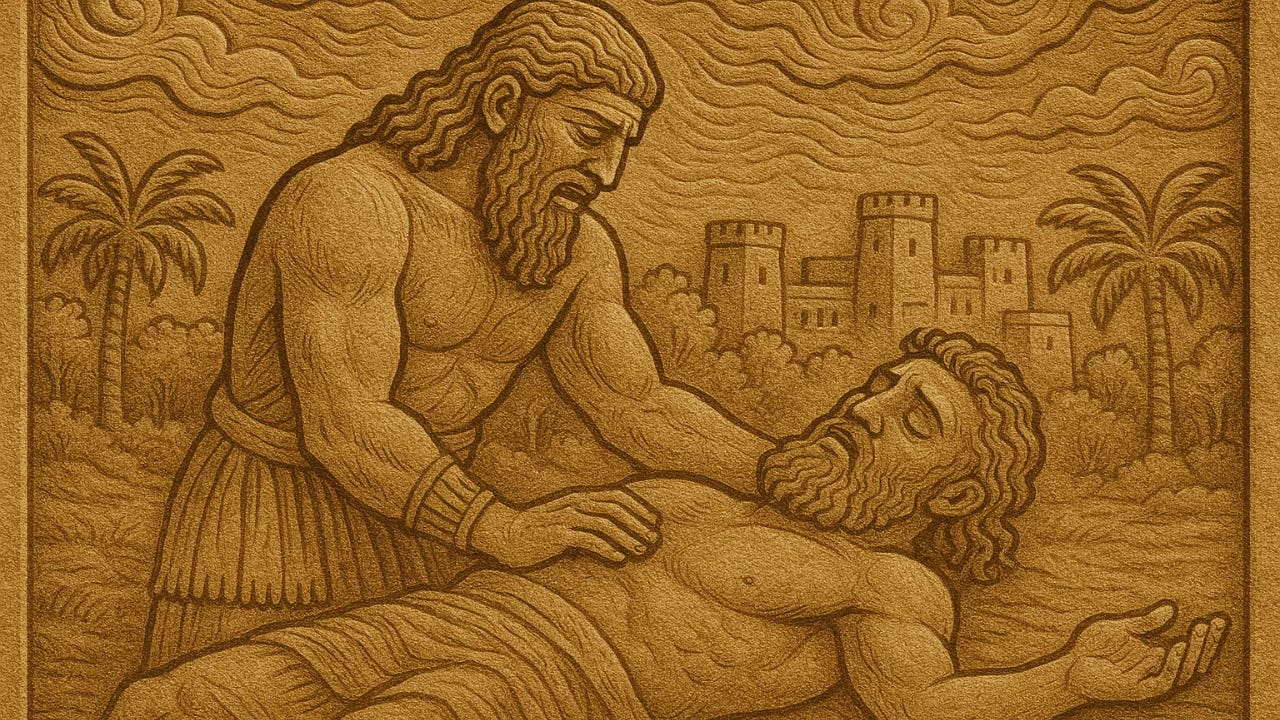

His people’s suffering eventually reaches the Gods, however, who decide to intervene by creating him an equal, namely Enkidu, a wild man meant to challenge and temper Gilgamesh’s excesses. Enkidu’s character serves to balance these excesses illustrated in the beginning of the story rather than a moral check on his behavior. For instance, their initial wrestling match, in which Gilgamesh emerges victorious, demonstrates his strength but does little to humble him, highlighting that Enkidu’s role is more companion than a moral corrective. Over time, their bond deepens, marked by loyalty, shared adventure, and intimacy, with homoerotic undertones that emphasize the emotional intensity of their connection.

Death and Mortality

Following Enkidu’s death, Gilgamesh reaches a turning point in his life. He is now confronted with the inevitability of death. Stricken by fear and grief, he embarks on a second journey. Now, he is seeking to escape the limits of human life. On his quest for immortality, he meets Utnapishtim, a survivor of a great flood. Through failed trials and the loss of a youth-restoring plant, Gilgamesh learns that humans cannot escape death. This realization reshapes his perspective, emphasizing reflection, leadership, and the enduring impact of his actions over the pursuit of personal immortality.

Legacy and Selective Memory

Ultimately, Gilgamesh returns to Uruk. His legacy and memory emerge as central concerns in the Epic of Gilgamesh. The grandeur of Uruk’s city walls reflects pride in communal achievements, while Enkidu’s construction of the Cedar Gate provides a tangible mark of contribution. Gilgamesh’s immortality in this sense is secured not through justice or moral reckoning, but through the epic itself, which preserves his story and deeds. This emphasizes the tension between personal flaws and enduring legacy, highlighting how memory can celebrate accomplishments while overlooking ethical failings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, The Epic of Gilgamesh presents a complex portrait of a flawed hero whose journey explores friendship, heroism, mortality, and legacy. While Gilgamesh’s tyranny and moral failings remain largely unaddressed, his experiences, particularly his bond with Enkidu and his confrontation with death, shape a deeper understanding of human limits and the pursuit of meaning. This omission raises a critical question: does cultural memory glorify power without demanding moral accountability? Perhaps the true lesson is not only that death is inevitable, but also that cultural memory itself is selective, preserving legacies while overlooking injustices. Ultimately, the epic privileges personal grief and emotional growth over communal justice, reflecting Mesopotamian values of heroism and legacy but clashing with modern ethical expectations.